13.2. Asynchronous Computation¶ Open the notebook in SageMaker Studio Lab

Today’s computers are highly parallel systems, consisting of multiple CPU cores (often multiple threads per core), multiple processing elements per GPU, and often multiple GPUs per device. In short, we can process many different things at the same time, often on different devices. Unfortunately Python is not a great way of writing parallel and asynchronous code, at least not without some extra help. After all, Python is single-threaded and this is unlikely to change in the future. Deep learning frameworks such as MXNet and TensorFlow adopt an asynchronous programming model to improve performance, while PyTorch uses Python’s own scheduler leading to a different performance trade-off. For PyTorch, by default, GPU operations are asynchronous. When you call a function that uses the GPU, the operations are enqueued to the particular device, but not necessarily executed until later. This allows us to execute more computations in parallel, including operations on the CPU or other GPUs.

Hence, understanding how asynchronous programming works helps us to develop more efficient programs, by proactively reducing computational requirements and mutual dependencies. This allows us to reduce memory overhead and increase processor utilization.

import os

import subprocess

import numpy

import torch

from torch import nn

from d2l import torch as d2l

import os

import subprocess

import numpy

from mxnet import autograd, gluon, np, npx

from mxnet.gluon import nn

from d2l import mxnet as d2l

npx.set_np()

13.2.1. Asynchrony via Backend¶

For a warmup consider the following toy problem: we want to generate a

random matrix and multiply it. Let’s do that both in NumPy and in

PyTorch tensor to see the difference. Note that PyTorch tensor is

defined on a GPU.

# Warmup for GPU computation

device = d2l.try_gpu()

a = torch.randn(size=(1000, 1000), device=device)

b = torch.mm(a, a)

with d2l.Benchmark('numpy'):

for _ in range(10):

a = numpy.random.normal(size=(1000, 1000))

b = numpy.dot(a, a)

with d2l.Benchmark('torch'):

for _ in range(10):

a = torch.randn(size=(1000, 1000), device=device)

b = torch.mm(a, a)

numpy: 1.4693 sec

torch: 0.0022 sec

The benchmark output via PyTorch is orders of magnitude faster. NumPy dot product is executed on the CPU processor while PyTorch matrix multiplication is executed on GPU and hence the latter is expected to be much faster. But the huge time difference suggests something else must be going on. By default, GPU operations are asynchronous in PyTorch. Forcing PyTorch to finish all computation prior to returning shows what happened previously: computation is being executed by the backend while the frontend returns control to Python.

with d2l.Benchmark():

for _ in range(10):

a = torch.randn(size=(1000, 1000), device=device)

b = torch.mm(a, a)

torch.cuda.synchronize(device)

Done: 0.0058 sec

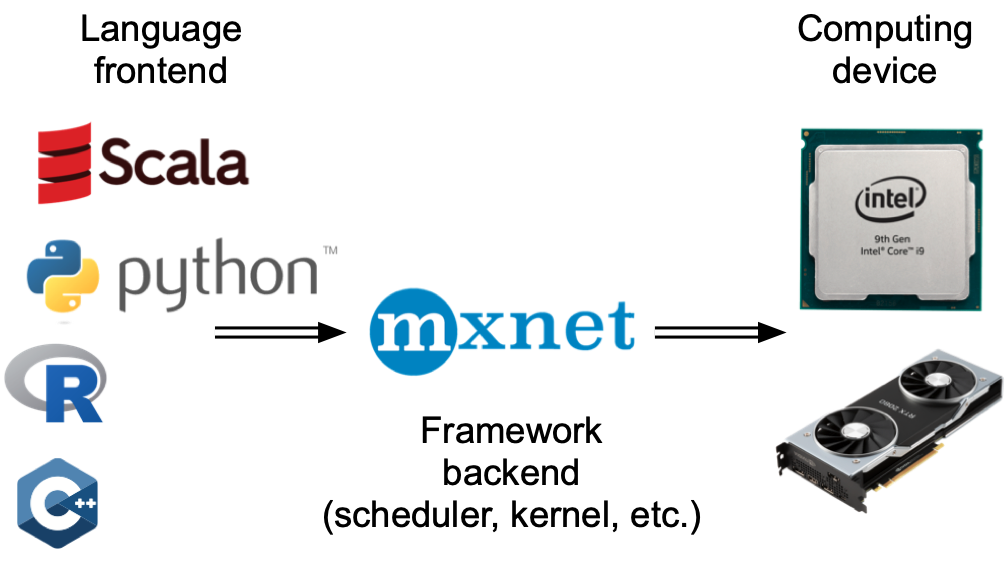

Broadly speaking, PyTorch has a frontend for direct interaction with the users, e.g., via Python, as well as a backend used by the system to perform the computation. As shown in Fig. 13.2.1, users can write PyTorch programs in various frontend languages, such as Python and C++. Regardless of the frontend programming language used, the execution of PyTorch programs occurs primarily in the backend of C++ implementations. Operations issued by the frontend language are passed on to the backend for execution. The backend manages its own threads that continuously collect and execute queued tasks. Note that for this to work the backend must be able to keep track of the dependencies between various steps in the computational graph. Hence, it is not possible to parallelize operations that depend on each other.

For a warmup consider the following toy problem: we want to generate a

random matrix and multiply it. Let’s do that both in NumPy and in

mxnet.np to see the difference.

with d2l.Benchmark('numpy'):

for _ in range(10):

a = numpy.random.normal(size=(1000, 1000))

b = numpy.dot(a, a)

with d2l.Benchmark('mxnet.np'):

for _ in range(10):

a = np.random.normal(size=(1000, 1000))

b = np.dot(a, a)

numpy: 0.8850 sec

mxnet.np: 0.0164 sec

[21:49:14] ../src/storage/storage.cc:196: Using Pooled (Naive) StorageManager for CPU

The benchmark output via MXNet is orders of magnitude faster. Since both are executed on the same processor something else must be going on. Forcing MXNet to finish all the backend computation prior to returning shows what happened previously: computation is executed by the backend while the frontend returns control to Python.

with d2l.Benchmark():

for _ in range(10):

a = np.random.normal(size=(1000, 1000))

b = np.dot(a, a)

npx.waitall()

Done: 1.4073 sec

Broadly speaking, MXNet has a frontend for direct interactions with users, e.g., via Python, as well as a backend used by the system to perform the computation. As shown in Fig. 13.2.1, users can write MXNet programs in various frontend languages, such as Python, R, Scala, and C++. Regardless of the frontend programming language used, the execution of MXNet programs occurs primarily in the backend of C++ implementations. Operations issued by the frontend language are passed on to the backend for execution. The backend manages its own threads that continuously collect and execute queued tasks. Note that for this to work the backend must be able to keep track of the dependencies between various steps in the computational graph. Hence, it is not possible to parallelize operations that depend on each other.

Fig. 13.2.1 Programming language frontends and deep learning framework backends.¶

Let’s look at another toy example to understand the dependency graph a bit better.

x = torch.ones((1, 2), device=device)

y = torch.ones((1, 2), device=device)

z = x * y + 2

z

tensor([[3., 3.]], device='cuda:0')

x = np.ones((1, 2))

y = np.ones((1, 2))

z = x * y + 2

z

array([[3., 3.]])

Fig. 13.2.2 The backend tracks dependencies between various steps in the computational graph.¶

The code snippet above is also illustrated in

Fig. 13.2.2. Whenever the Python frontend thread executes

one of the first three statements, it simply returns the task to the

backend queue. When the last statement’s results need to be printed,

the Python frontend thread will wait for the C++ backend thread to

finish computing the result of the variable z. One benefit of this

design is that the Python frontend thread does not need to perform

actual computations. Thus, there is little impact on the program’s

overall performance, regardless of Python’s performance.

Fig. 13.2.3 illustrates how frontend and backend interact.

Fig. 13.2.3 Interactions of the frontend and backend.¶

13.2.2. Barriers and Blockers¶

There are a number of operations that will force Python to wait for completion:

Most obviously

npx.waitall()waits until all computation has completed, regardless of when the compute instructions were issued. In practice it is a bad idea to use this operator unless absolutely necessary since it can lead to poor performance.If we just want to wait until a specific variable is available we can call

z.wait_to_read(). In this case MXNet blocks return to Python until the variablezhas been computed. Other computation may well continue afterwards.

Let’s see how this works in practice.

with d2l.Benchmark('waitall'):

b = np.dot(a, a)

npx.waitall()

with d2l.Benchmark('wait_to_read'):

b = np.dot(a, a)

b.wait_to_read()

waitall: 0.0180 sec

wait_to_read: 0.0189 sec

Both operations take approximately the same time to complete. Besides

the obvious blocking operations we recommend that you are aware of

implicit blockers. Printing a variable clearly requires the variable

to be available and is thus a blocker. Last, conversions to NumPy via

z.asnumpy() and conversions to scalars via z.item() are

blocking, since NumPy has no notion of asynchrony. It needs access to

the values just like the print function.

Copying small amounts of data frequently from MXNet’s scope to NumPy and back can destroy performance of an otherwise efficient code, since each such operation requires the computational graph to evaluate all intermediate results needed to get the relevant term before anything else can be done.

with d2l.Benchmark('numpy conversion'):

b = np.dot(a, a)

b.asnumpy()

with d2l.Benchmark('scalar conversion'):

b = np.dot(a, a)

b.sum().item()

numpy conversion: 0.0340 sec

scalar conversion: 0.0445 sec

13.2.3. Improving Computation¶

On a heavily multithreaded system (even regular laptops have 4 threads

or more and on multi-socket servers this number can exceed 256) the

overhead of scheduling operations can become significant. This is why it

is highly desirable to have computation and scheduling occur

asynchronously and in parallel. To illustrate the benefit of doing so

let’s see what happens if we increment a variable by 1 multiple times,

both in sequence or asynchronously. We simulate synchronous execution by

inserting a wait_to_read barrier in between each addition.

with d2l.Benchmark('synchronous'):

for _ in range(10000):

y = x + 1

y.wait_to_read()

with d2l.Benchmark('asynchronous'):

for _ in range(10000):

y = x + 1

npx.waitall()

synchronous: 3.1623 sec

asynchronous: 0.9288 sec

A slightly simplified interaction between the Python frontend thread and

the C++ backend thread can be summarized as follows: 1. The frontend

orders the backend to insert the computation task y = x + 1 into the

queue. 1. The backend then receives the computation tasks from the queue

and performs the actual computations. 1. The backend then returns the

computation results to the frontend. Assume that the durations of these

three stages are \(t_1, t_2\) and \(t_3\), respectively. If we

do not use asynchronous programming, the total time taken to perform

10000 computations is approximately \(10000 (t_1+ t_2 + t_3)\). If

asynchronous programming is used, the total time taken to perform 10000

computations can be reduced to \(t_1 + 10000 t_2 + t_3\) (assuming

\(10000 t_2 > 9999t_1\)), since the frontend does not have to wait

for the backend to return computation results for each loop.

13.2.4. Summary¶

Deep learning frameworks may decouple the Python frontend from an execution backend. This allows for fast asynchronous insertion of commands into the backend and associated parallelism.

Asynchrony leads to a rather responsive frontend. However, use caution not to overfill the task queue since it may lead to excessive memory consumption. It is recommended to synchronize for each minibatch to keep frontend and backend approximately synchronized.

Chip vendors offer sophisticated performance analysis tools to obtain a much more fine-grained insight into the efficiency of deep learning.

Be aware of the fact that conversions from MXNet’s memory management to Python will force the backend to wait until the specific variable is ready. Functions such as

print,asnumpyanditemall have this effect. This can be desirable but a careless use of synchronization can ruin performance.

13.2.5. Exercises¶

On the CPU, benchmark the same matrix multiplication operations in this section. Can you still observe asynchrony via the backend?

We mentioned above that using asynchronous computation can reduce the total amount of time needed to perform 10000 computations to \(t_1 + 10000 t_2 + t_3\). Why do we have to assume \(10000 t_2 > 9999 t_1\) here?

Measure the difference between

waitallandwait_to_read. Hint: perform a number of instructions and synchronize for an intermediate result.